Blood of the Oak by Eliot Pattison

14 December, 2016

Some of you may recall my love of Eliot Pattison’s Tibetan mysteries beginning with The Skull Mantra featuring Inspector Shan, a disgraced Chinese policeman exiled to Tibet. Pattison’s use of the mystery genre to convey the beauty and tragic history of Tibet is one of the few series that manages to portray the fierce resilience and compassion of the Tibetan people in the face of annexation and oppression. Pattison is also the author of a series set in colonial America before independence and I was keen to try it.

Blood of the Oak is the fourth volume of Pattison’s Bone Rattler series and features Duncan McCallum, an indentured Scot in colonial America. It is 1765 and Duncan, now living in Edentown with his partner Sarah Ramsey and his friend Conawago, a Nipmuc, is summoned by Adanahoe, an Iroquois elder, to investigate the theft of a sacred mask. Having earned their trust and because of his medical training, Duncan is known by the Iroquois as the Death Speaker, a rarity amongst the Europeans.

America is in the throes of conflict, a burdgeoning sense of independent identity is forming amongst a small group of influential men and women and resistance is growing against the English and the French who are keen to lay claim to the rich lands held sacred by the Native American tribes. They find themselves caught in the middle, used and discarded by both sides, wary of the Europeans, desperate to protect themselves. When Duncan’s search for the mask leads him to an injured ranger, his friend Patrick Woolford, he realises he has stumbled upon another mystery. When Woolford tells him 19 men have gone missing from Benjamin Franklin’s fledgling communications network including some of his own rangers, Duncan knows they are facing an incredibly clever and terrible foe. For Woolford, like Duncan and the Iroquois, is an expert in navigating the forests.

As the powerful elite in England try to cement their control over their wayward colony through the Stamp Tax, Duncan is drawn into the power play that threatens everything he holds dear. As he begins his journey with his friend Tanaqua, a Mohawk, and Analie, a French orphan, to try and prevent the brewing catastrophe, he will come face to face with evil from his past. What is at stake here is not just the lives of those dear to him but the state of the nation itself. But where there is evil, there will be resistance and Duncan finds himself in the midst of those who are willing to put aside differences to fight together for their rights.

As well as tackling the complex nature of the different resistance groups supporting the revolutionary cause, the sheer number of people who risked their lives from the Scottish, the English, all the Native American tribes and the African American community, from the freedmen to those struggling under the chains of slavery, Pattison draws an intricate portrait of colonial America and the high stakes involved. The fragility of freedom, the long yoke of servitude and indenture, the indignities, torture and injustice suffered by so many because of the misplaced belief that one race, one people, one class can be better than another is a polemic that is familiar and should still be feared today. And that the only way to overcome the odds is to work together towards a common goal which Pattison shows beautifully.

Like his Tibetan novels, Pattison pulls off an intricate mystery while building a world in which historical figures come alive. The complexity of his characters, each with a difficult past, each making their own hard choices, show how tough it was to survive in the new land. And yet within such chaos also lie scenes of stillness and beauty, of the power and sanctity of nature, the importance of belief and worship, and ultimately what ties you to your identity. Pattison excels in creating a story that combines mystery with politics, history and adventure, but what I like best about his novels are his compelling characters. Although some of the characters may be a little too cut and dry, especially the antagonists, Pattison avoids too much stereotyping by including a whole spectrum of characters and he doesn’t shy away from showing the ugly side of society in each community. And like his Tibetan novels, making an outsider, in this case Duncan, the central character makes it work. It certainly sets one thinking about how history and cultures are recorded and by whom.

Although this novel could be read as a standalone, I enjoyed it so much that as soon as I finished it, I ordered the rest, Bone Rattler, Eye of the Raven and Original Death. As much as it is a mystery, it is also a love letter to the Native American tribes as well as the exiled Scots who only wanted a place in which to live free.

My knowledge of Native American history is pretty much limited to James Fenimore Cooper’s oft-criticised The Last of the Mohicans set in the same period, and reading this has re-awakened my interest. As well as the bibliography in Blood of the Oak, I have Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown and The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and any further recommendations would be greatly welcome.

I would like to thank Eliot Pattison for kindly offering me this book for review. He was right in saying this was a topical and timely read, especially in the wake of recent world events. It would do America and the rest of the world good to go back and re-assess the reasons why people fought so hard for independence in so many countries around the world and that we mustn’t forget that liberty, equality and justice are rights we cannot afford to discard.

For Two Thousand Year by Mihail Sebastian

7 April, 2016

You can find my review of Mihail Sebastian’s beautiful novel For Two Thousand Years in Issue 9 of Shiny New Books! out today. Please do go and have a look!

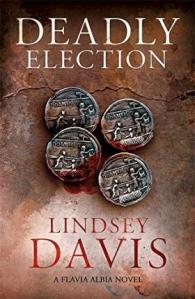

Deadly Election by Lindsey Davis

30 March, 2016

As you all probably know, I am a huge fan of Lindsey Davis’ Falco series set in Vespasian’s Rome. Her follow-up series with Falco’s adopted British daughter Flavia Albia, though a little darker in tone due to Rome being under the brutal thumb of Domitian, has firmly hit its stride.

In her third outing, Deadly Election, Albia is caught in the middle of a Roman election whilst trying to identify a decomposing corpse that falls out of a locked chest from Pompeii belonging to Callistus Valens in the middle of a highly publicised auction at her family’s auction house. Together with her new friend and magistrate Manlius Faustus, currently campaign manager for his childhood friend Vibius who is standing for the office of aedile at the elections, Albia delves deeper into the mystery of the dead body found bound and stuffed into the chest. As she unravels the strangely intricate familial ties between the sellers of the chest of death and the various electoral candidates, she comes up against a formidable political family headed by Julia Verucanda, ‘the mother-in-law from Hades’. As the death count mounts in the hot July summer, Albia and Faustus find themselves caught in a deadly web that spans generations.

Once again, Davis has delivered a highly enjoyable and educational mystery. I raced through Deadly Election as with all her other books, stopping once in a while to wonder at her deft characterisation and her beautiful rendering of a living, breathing ancient Rome. You can see how much she loves Rome with all its complex social hierarchies, variety of peoples from all over the empire and the deadly politics that underpinned Roman life. I love the characters of Albia, who is a mature, independant woman who has seen enough of the harshness of life to appreciate what is truly precious, and Faustus, a serious, upright citizen with a soft spot for Albia. I like a bit of romance in my mysteries and Davis has drawn this one out long enough for you to care about both characters. Domitian doesn’t make an appearance here but he is always present, a constant threat in people’s lives.

If you haven’t tried Davis’ mysteries, I urge you all to start. I like reading a series in order so would recommend you start with The Silver Pigs. However there are over 20 mysteries in the Falco series which are all separate mysteries but follow a slow chronological arc where you see the evolution of his relationships and family. Part of the joy of reading a series is seeing how the characters develop, and Davis is particularly good at this.

If you want to start with Flavia Albia’s series, that is fine too, although I feel you will enjoy it more from dipping into some of the books in the Falco series first. The titles in the Flavia Albia series so far:

As Chimney Sweepers Come to Dust by Alan Bradley

22 March, 2016

Alan Bradley’s seventh novel featuring the magnificent 11 year old chemist Flavia de Luce comes after the satisfying conclusion of a six book long story arc which culminated in the revelation of Flavia’s mother, Harriet’s, fate. This led to Flavia being inducted into some special secrets and what she sees as her ‘banishment’ from her beloved home, Buckshaw, in the lovely English village of Bishop’s Lacey. We start As Chimney Sweepers Come to Dust with Flavia reluctantly on her way to Harriet’s old boarding school, Miss Bodycote’s Female Academy in Canada, to be finished.

The night Flavia arrives at Miss Bodycote’s, she is rudely awoken by a fellow student quickly followed by a dessicated corpse that comes tumbling down from her chimney wrapped in the school’s Union Jack flag. The student is taken away in shock but Flavia keeps her cool and secretes a medallion that has broken loose from the grisly corspe before she is bundled away to sleep in the Headmistress’ living room. The incident is played down and yet there are strange rumours of missing girls and ghosts. As Flavia tries to adjust to her new surroundings and get acquainted with her fellow boarders, she begins to suspect that not all is as it seems at Miss Bodycote’s. Her Aunt Felicity had sent her here to learn the tricks of the trade in order to follow in her mother’s footsteps so Flavia knows this school is nothing but ordinary. However, the air is thick with secrets and the Chemistry teacher, to Flavia’s delight, is an acquitted murderer. Will she get to the bottom of the mystery? Whose corpse is it and why does no one speak of the missing girls?

As Chimney Sweepers Come to Dust is as delightful as all the other novels in the series. Bradley’s principal characters are so well drawn that I really missed Flavia’s family in England as much as she did. Although there have been some reviews decrying Flavia’s jaunt across the pond, I really enjoyed the rarified and insular air of the girls boarding school which brought back happy memories but with all the twisted friendships and secrets that are part and parcel of boarding school life. Flavia, who normally only has her sisters and the people in her village to keep her company, is suddenly thrust into this new world in which she has to make new friends but be alert enough to know whom to trust. And for someone who likes not to be too noticeable, she is also the daughter of Harriet who is revered like a god at Miss Bodycote’s.

All of Flavia’s schoolmates were given interesting names and characters and apart from one niggling point about a missing girl which didn’t seem to be sufficiently explained, the mystery was pretty good. But what keeps drawing me back to Bradley’s creation is Flavia and her family. Flavia’s pluckiness, this time combined with a barely held back home-sickness, just made me want to go and give her a big hug. And what makes reading these books so enjoyable is you can feel how much fun the author is having writing them. I’m already looking forward to the next book in the series.

Other books in the series:

The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie

The Weed that Strings the Hangman’s Bag

A Red Herring Without Mustard

I Am Half Sick of Shadows

Speaking From Among the Bones

The Dead in their Vaulted Arches

Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison

11 December, 2015

We’ve certainly had a run of incredibly good books for our book group choices this year. Last month’s book, Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison, was one I hadn’t heard of before but the cover was so gorgeous I had to go and get myself a physical copy of the book instead of a kindle download. Don’t you love it when a cover hooks you like that?

There was also a recommendation from Barbara Kingsolver, one of my favourite writers and author of The Poisonwood Bible, which also further provoked my interest and she wasn’t wrong. Bastard Out of Carolina isn’t an easy read but it is brilliant. Brilliant because Allison manages to keep the tension simmering just below the surface, occasionally unleashing it, and then dropping in scenes of such domestic love and comfort that you forget the danger that lurks just behind the half-closed door.

Set in Carolina in the 50s, Allison’s novel centres on a large white-trash family with colourful characters and histories who love and fight their way through life. Our heroine Bone is the illegitimate daughter of teenage Mama, the youngest and fairest of her large, boisterous family. There are no ends to suitors but she falls for a charmer traveling through town who vanishes as soon as she gets pregnant. Nevertheless determined to correct Bone’s birth certificate, she faces the moral contempt of self-righteous officials at the town hall who refuse to change Bone’s legal status but she keeps trying year after year. Then she falls in love and marries a sweet young man who is ready to adopt Bone but who meets with an accident and Mama is left grieving with two little girls. Forsaking love, she works at the local diner until her brother Earl brings Glen, an intense young colleague who is the outcast son of a well-to-do local family with daddy issues. Glen is patient and woos Mama over a year and she gradually falls in love with this brooding young man who has been so starved of love and decides to marry him only after he promises to love both her and her girls. Blinded by her love for him, she fails to acknowledge his many complexes, especially when he cannot hold down a steady job without getting into fights. But Glen loves her and she loves him and they both believe that it will all come together. That is until tragedy strikes.

It’s pretty early on in the novel, but this loss coincides with a shocking incident that will completely derail the reader. Up until then, you may be forgiven if you think Bastard Out of Carolina is all about big families and poverty. The novel takes a decidedly darker tone and you see what menace lurks beneath the surface. Allison tackles the fragile structures of love and families through the secrets we keep from each other. And throughout this, the crux is Bone, so young, so alone and trying desperately to keep her small, precious family from falling apart. What Allison does so brilliantly is intersperse scenes of Daddy Glen’s anger within their nuclear family with the warm, protective nature of Bone’s extended family with her larger than life aunts and uncles who would do anything to protect their kin. This doesn’t mean that they don’t have problems of their own, what with their fighting, alcohol abuse and infidelities all casting a shadow across their lives. And yet they are in stark contrast to the cold, unwelcoming family in which Daddy Glen grew up and to whom he stubbornly brings his little family once a year to visit whether they like it or not.

As a psychological study, Daddy Glen is a classic case of the youngest son who didn’t grow into his potential and who is forever trying to please his successful father and two older brothers. But the most interesting character in this novel is Mama, who stays with Daddy Glen even though she knows things are not quite right in their house. Even after witnessing his harsh punishment for Bone’s adolescent transgressions, she makes a half-hearted effort to leave him but returns when he begs for forgiveness. For Daddy Glen, Mama is the love of his life. And so it becomes even harder to understand the motives behind his actions, even if you look to his unhappy childhood.

The bits that I liked the most were those describing Mama’s family. You see her bond with her siblings, their love for each other coming through so strongly at family gatherings, holidays and over food. The colourful histories of each individual are so captivating that you wish you were a part of their brood. And yet they weren’t enough to shield Bone.

Bastard Out of Carolina, like all the best books, leaves you with even more questions at the end. It’s dark and devastating but pierced with moments of such warmth and joy, that it will remain long in your heart. The inevitable ending may be more than you can bear but what happens after will truly break your heart.

Allison says that so many of her readers have told her that she has written their story and we can see why. She gets into the head of Bone so well, putting into words the confusing, constantly shifting feelings of fear, pain and anger which a child cannot fully express. She doesn’t sentimentalise or rationalise these thoughts, she just puts them down as they are. When everything is stripped away, what remains is Bone’s resilience. Although not autobiographical, nevertheless we can see parallels to Allison’s own childhood. Perhaps what she really wanted to explore was her mother’s choices. I’m not a fan of depressing novels and I read this was trepidation, dreading what was to come, but such is the power of Allison’s writing that I couldn’t keep myself from finishing this incredible novel.

The Grass is Singing by Doris Lessing

3 November, 2015

August’s book group choice by Kim was Doris Lessing’s debut novel published in 1950, The Grass is Singing. A Nobel Prize Laureate and author of many novels including The Golden Notebook, I had heard so much about Lessing and yet felt slightly afraid to read her.

The Grass is Singing is set in Southern Rhodesia in the 1940s and begins with the murder of Mary Turner by her black servant Moses. In a land where strict racial rules are the means by which the white colonisers maintain their control, any untoward issues that don’t fit in with white society’s ideas of how people should act is quickly and unsentimentally cleared away, untouched. Mary’s murder is cleared as one catalysed by greed. But what Lessing does so beautifully here is to go back in time to find out who Mary Turner was to see why she had to die. And what unravels is a tense, bleak tale of a woman, once happy in her independance and freedom, who is gradually stifled and suffocated by society’s expectations and petty rules.

Free at last from her poverty-stricken childhood, a young Mary is living a happy and carefree life in town, working as a secretary and living in a girls hostel where she is never without friends and things to do. She is happy to carry on in this way, having no need for a husband or a house of her own until she overhears her friends ridiculing her behind her back. This sudden shock instigates a paradigm shift in her world view and sets her on a course which she may not have otherwise chosen. She is nothing if not proactive and immediately changes the way she dresses and goes on several unsuccessful dates, making her unhappy and suspicious of other people’s motives. That is until she meets Martin Turner, up in town for the day, a shy, awkward young man who spends most of his time alone working on his farm. Although they feel no attraction to each other, nevertheless, Martin is lonely and Mary needs to get married, and so this happens before they get to really know one another. Mary is happy to leave the town that has soured and Martin is eager to start a family once he has made his farm profitable and has enough money. But life on a farm in the middle of nowhere is far from the life Mary ever envisioned for herself, as is the lack of money. Martin is kind, if not stubborn, but the evergrowing failures of all his ventures quickly grinds down her respect for him. Mary is also uncommunicative and cold and Martin soon realises that his idea of a warm family life may never materialise. And yet the two continue in this vein, Mary slowly succumbing to ennui and depression as the heat gets to her, ever relentless, and her encounters with the natives who work for Martin are fraught with suspicion and trouble. The two are bound together in their wretched house, isolated, and what happens is a slow disintegration of will.

Until Moses, one of Martin’s workers, comes to work for Mary in the house. His arrival acts as catalyst, suddenly awakening Mary out of her stupor and bringing up complex emotions that highlights the subtly fraught relations that exist between servant and master, family and friend.

And then there is Charlie Slatter, Martin’s neighbour and local kingpin who overseas the social and agricultural goings on in the area. He is the one whom they contact first when Mary’s body is found. He is the one organising and directing the police sergeant who arrives later. And he is the one who makes sure that no extra detail is leaked to the papers. For his duty is to keep the status quo and protect their own.

In The Grass is Singing, Lessing binds together a number of important issues; the segregation and treatment of the natives, the unspoken social rules from which you cannot veer and the limited roles within which women can exist in that time. For Mary, she was doomed if she didn’t get married, and she was doomed when she did. What is perhaps poignant is that ultimately both Mary and Martin aren’t exactly bad people. Martin is generally friendly towards his native workers, with a deep understanding of how things work in his country, if not his occupation. Mary starts off carefree, independant and happy, and probably her sole mistake is to get hitched without really thinking things through. What the the pair want are two different things, and because they are gauche and awkward at communicating, are like two cars just missing each other in the fog. Unable to really talk, they just keep diverging in thought and deed.

Lessing has created an incredibly nuanced yet striking novel. But there are so many questions which remain unanswered. What exactly was Mary’s relationship with Moses? What at first seemed as though it could have been a forbidden attraction turned out just to be fear. And yet, it was more than that. Charlie Slatter may have tried to tidy the murder as one committed by an angry and greedy servant, yet Moses’ feelings for Mary, although at the end seemed to be of power, had something more. What was it? Mary, though she needed Moses for her survival, much, much more than Martin, could never overcome her fear of him. And Moses, who knew he had power over her, didn’t leave because he knew she needed him. This strange, complex power relationship rings so true because it is pretty much the essence of relationships in its basic form. It stuns me to think that Lessing is able to convey this together with that of a marital couple, friends and neighbours to produce such a layered first novel. And leaving the central question unanswered may have been a stroke of genius. For what remains puzzling is precisely what will stay with you long after you’ve finished.

Lessing’s novel is nothing less than a novel about power in its many nuanced form. And she does this subtly and beautifully.

Spring Snow by Yukio Mishima

30 September, 2015

The Shinkawas were both irritated and flattered by the Matsugae’s invitation to the blossom viewing. Irritated because they realized how bored they would be. Flattered because it would give them an opportunity to display their authentically European manners in public. The Shinkawas were an old and wealthy merchant family and while it was, of course, essential to maintain the mutually profitable relationship established with the men from Satsuma and Choshu who had riesen to such power within the government, the Baron and his wife held them in secret contempt because of their peasant origins. This was an attitude inherited from their parents, and one that was at the very heart of their newly acquired but unshakable elegance.

Reading a novel by Yukio Mishima is rather a daunting prospect as he comes with a lot of baggage, from his highly sensationalised life and death to very divided opinions on his work amongst his Japanese readers. However, what can’t be disputed is his place in Japanese literature. He missed getting the Nobel Prize to Yasunari Kawabata, one he felt was unfair but perhaps inevitable in Japan’s strict hierarchical society even in literary circles, and some say this may have led to his inevitable foray into nationalism and death. But my mother told me many years ago that Mishima’s writing was beautiful and that I must read him. And so I chose him for my book group this summer.

Spring Snow is the first volume in Mishima’s Sea of Fertility quartet detailing the bittersweet love story between Kiyoaki Matsugae, son of a recently elevated Marquis at the Emperor’s court and coming from a long line of Satsuma samurai, and Satoko Ayakura, daughter of a waning aristocratic family, and how it reflects the seismic changes within Japanese society at the beginning of the 20th century. Following the Meiji Restoration, the power structure shifted from the samurai families back to the aristocracy once peace was established. The Marquis Matsugae had sent Kiyoaki to be educated in the Ayakura household and as a result, they no longer have anything in common, Kiyoaki having grown into a rarefied and refined gentleman studying at the Peers School until he is given a position at Court unlike his friend Honda, who has no privileged family connections and is studying to become a lawyer like his father. Into this friendship comes Satoko, Kiyoaki’s childhood friend, a beautiful and self-assured young woman, a few years older than Kiyoaki, who is in love with him. But Kiyoaki has been trained to contain all displays of emotions, fooling everyone around him and ultimately himself.

When Satoko’s engagement to an Imperial Prince is announced, Kiyoaki suddenly realises his love for her and is desperate to see her. With the help of Iinuma, his servant, and Tadeshina, Satoko’s maid who has worked for the Ayakuras since before Satoko’s birth, Kiyoaki sets in motion events which will have severe repercussions for both families.

This sounds rather grim and there are echoes of Romeo and Juliet here, however, it is Mishima’s style and his beautiful writing that elevates and transforms this tale into something so much more. Here is a microcosm of aristocratic Japanese society, still reverberating from the Meiji Restoration. Satoko, however spirited and intelligent and emotionally so much more mature that Kiyoaki is nevertheless bound by her family and society’s rules and makes the only choice available to her. We see her living, loving and finally realising the true metal of her lover, and although harsh, the choices she makes are the only ones which will set her free. Apart from Satoko, whose only flaw is to fall in love with Kiyoaki, most of the other characters are ineffectual and don’t realise their mistakes until the end. Kiyoaki’s parents are weak and blind to his faults and believe money will solve everything; Honda, Kiyoaki’s friend, tries to help but is too in awe of him; the Ayakuras are living off others and are consequently in a bubble; Iinuma, fanatical and unable to fit into Tokyo life; and Tadeshina, supposedly loyal with a cruel streak inside.

Mishima brilliantly depicts the subtle undercurrents within Satoko and Kiyoaki’s circle. The importance of keeping face as opposed to the often ugly side of reality, the obsession with strict rules and manners when real communication between people are lacking and most importantly, intent over-ridden by duty. Both Satoko and Kiyoaki try to break free from their restraints but their methods differ and ultimately fail. There is a tragic sense of miscommunication leaving the reader feeling, ‘if only he had’ or ‘why didn’t he just say something?’ This puts the onus on Kiyoaki, but it’s by no means only his fault. Satoko, who should have known him best failed too. All in all, it’s a glorious piece of tragic storytelling mixed in with cultural and historical detail. Mishima’s knowledge of history and his curiosity of other cultures are evident too. But what really strikes the reader is his mastery of language. His prose is light, whimsical and exquisite. And yet he delves into such dark themes. I loved this book which is so beautifully translated by Michael Gallagher and am looking forward to reading the other novels in the quartet, Runaway Horses, The Temple of Dawn and The Decay of the Angel.

I read this as part of Bellezza’s Japanese Literature Challenge 9. Do also check out the reviews by Kim and Tony.

Q&A: Aliette de Bodard

24 September, 2015

In the late twentieth century, the streets of Paris are lined with haunted ruins, the remnants of a Great War beween arcane powers. The Grands Magasins have been reduced to piles of debris, Notre-Dame is a burned-out shell, and the Seine has turned black with ashes, rubble, and the remnants of the spells that tore the city apart. But those who survived still retain their irrepressible appetite for novelty and distraction, and the great Houses still vie for dominion over France’s once-grand capital.

Once the most powerful and formidable, House Silverspires now lies in disarray. Its magic is ailing; it founder, Morningstar has been missing for decades; and now something from the shadows stalks its people inside their very own walls.

Within the House three very different people must come together: a naïve but powerful Fallen angel; an alchemist with a self-destructive addiction; and a resentful young man wielding spells of unknown origin. They may be Silverspires’ salvation or the architects of its last, irreversible fall. And if Silverspires fall, so may the city itself.

Aliette de Bodard’s new novel, The House of Shattered Wings, set in a 20th century post-apocalyptic Paris filled with fallen angels and mortals vying for power while something dark and dangerous is slowly picking them off, is a wonderful blend of fantastical elements from both Western and Eastern mythologies. I’ve been a huge fan of her work for a number of years and love her stories set in the Xuya universe and her Obsidian and Blood trilogy set during the Aztec Empire of which Servant of the Underworld is the first volume.

Upon reading her latest novel, I sent her a number of questions which she was kind enough to answer. Enjoy!

1. In The House of Shattered Wings, which character did you most connect with and who did you most enjoy writing about?

That’s a bit like asking me to pick a favourite child! I really like all the characters in the book (even though they might not like me, as I put them through a bit of a ride!). I particularly connect with Madeleine, the House alchemist, who is a bit of a geek and inept at social situations (the scene where she attempts to play high-level politics and fails was something that was very familiar to me!). The character I enjoyed writing about the most is actually head of House Hawthorn and part-time antagonist Asmodeus – I certainly wouldn’t like to have a drink with him or trust him with much of anything, but as a writer he’s great to put in scenes because of all the snarky comebacks. Also, the fact all three main characters distrust him, fear him and/or hate his guts make him a great plot mover and generator of conflict.

2. What were your inspirations for the novel?

I had a lot of inspirations for the novel: part of it is my love letter to 19th Century novels (Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, Hugo’s Les Misérables, Zola), part of it draws from manga and anime (I took some lessons in period drama and creepy monsters from Full Metal Alchemist, and also took some inspiration from Black Butler‘s alternate and phantasmagoric Victorian England), and part of it is classic fantasy of people doing small and epic things against overwhelming odds (David Gemmell’s King Beyond the Gate and the other Drenai novels, and books by Elizabeth Bear, Kari Sperring, Tim Powers, China Miéville and many others!). And finally part of it is fairytales and myths from Vietnam my grandmother used to tell me when I was a child.

3. Could you tell us something about your writing rituals? Do you create as you go along or plot meticulously?

I am a methodical plotter and I tend to do very badly without an outline (translate by ‘flailing around and moaning a lot’!). I generally do a chapter by chapter, scene by scene outline which I use as a basis for launching into the book. It tends to be a bit vaguer as we get close to the end (one book in the Obsidian and Blood series memorably had ‘somehow, they win the day’ to cover the last three chapters of epic battles!), and I also tend to heavily rework out as I go. For instance, The House of Shattered Wings originally had Madeleine returning of her own will to House Hawthorn, and this bit ended up not making sense at all, so I changed the timeline of the last three chapters. The ending (I won’t go into it because spoilers!) was also one of those totally unplanned things that ended up looking as though it’d been there all along – it was kind of a relief and kind of scary, actually – felt like my muse and unconscious had been working double time while I was desperately trying to get the last chapters working!

I write when I can, which means when the infant isn’t taking up all the space in my life: I do a lot of first drafting on the metro while commuting, and a lot of revisions in the evenings or on weekends. I am a slow first drafter, but I revise pretty fast fortunately (and don’t quite need as much brain space and immersion), so that helps!

4. I love that you incorporate other cultures in your work, especially your Xuya Universe and the Mexica Empire in your Obsidian and Blood trilogy, and I want to read more. What sparks your interest and how do you go about your research?

I’ve incorporated other cultures in my work because I feel the need to bring fantasy beyond Western, pseudo-European cultures, and draw inspiration from further afield. Part of it comes from growing up away from the mainstream and with a different culture – I feel like, in many ways, I’m always writing for ten-year-old me, who was so desperate for anything Asian that she devoured anything with dark-haired, short women in them.

I also think a lot of it (particularly the Chinese in the Xuya universe) was my way of circling Vietnamese culture and never quite bringing myself to write about it because I was scared I wouldn’t do it justice! (And I was already imagining my entire maternal family coming down like a ton of bricks on me). It took a conversation with my good friend Rochita Loenen-Ruiz to realise that if I didn’t do it, who else would?

I do research with a variety of sources: primary sources, academic texts, fiction–and people (for Obsidian and Blood I didn’t do that last and it was a mistake).

5. And what are some of your favourite books and authors?

Ha, too many to be listed! I really love Terry Pratchett: I own all the Discworld books and come back to them from time to time, like old friends. Recently I’ve enjoyed Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem, a combination of hard SF and Chinese history that is mindblowing (and I’m looking forward to The Dark Forest), Elizabeth Bear’s Range of Ghosts, an epic fantasy set in an analogue of the Silk Road, J Damask’s Jan Xu books, wonderful family-focused urban fantasy set in Singapore, and Sergey and Marina Dyachenko’s The Scar, a dark and intense fantasy about a man’s search for redemption in the aftermath of a magical war.

Thank you so much to Aliette for providing such fabulous answers. I will certainly be checking out her incredibly diverse list of books and will be waiting with bated breath for the sequel to The House of Shattered Wings.

The House of Shattered Wings by Aliette de Bodard

21 September, 2015

Fallen blood is power.

Aliette de Bodard is one of the new breed of writers ushering in a welcome change in the SFF literary community with her stories set in the Xuya universe, a brilliant coalescence of Western SF traditions and her mixed Vietnamese background, so compelling and beautifully written. She is also the author of the Obsidian and Blood trilogy, murder mysteries set in the Aztec Empire beginning with Servant of the Underworld, a series I love tremendously for its ability to immerse you in an utterly foreign culture with a completely different set of rules and a religion in which magic plays an important part. If you haven’t read her fiction already, I urge you to try.

In her new book, The House of Shattered Wings, she tries something different. Set in a post-apocalyptic Paris forsaken by God, there exists a fragile equilibrium controlled by the Houses, structured communities of fallen angels and humans, of which the three strongest are Silverspires, Hawthorn and Lazarus. The novel is set sometime in the 20th century, many years after the Great Houses War which destroyed most of Paris leaving it an empy hull with pockets of surviving communities, the safest being the Houses protected by the Fallen, of whom Lucifer Morningstar is the most powerful. But it’s been 20 years since Morningstar’s disappearance and his successor, Selene, is still struggling to overcome her doubts in taking charge of Silverspires, once the grandest of the Houses.

Every so often, a newborn Fallen is thrust out of Heaven and lands in a part of Paris and there is a race to retrieve him or her. If a House gets her, she will become a strong ally, if a Houseless gets to her, she will be harvested for her magic, every inch of her skin, bone and flesh used to ingest, produce and barter, a sick but lucrative trade. When Selene saves Isabelle, a newly Fallen, she also captures Philippe, a mysterious Annamite with hidden powers, a member of a Houseless gang. When he unwittingly unleashes a malevolent spell, Silverspires is drawn into complex game of survival. For something or someone is determined to destroy Morningstar’s legacy, leaving behind a trail of corpses. As Selene, together with Isabelle, Philippe and Madeleine, the House alchemist with a secret of her own, struggles to contain the darkness, can they stop the darkness which threatens the very safety of Paris itself?

One of the first things that you encounter as you read this tale is Bodard’s striking vision of Paris.

The Grands Magasins have been reduced to piles of debris, Notre-Dame is a burned-outshell, and the Seine has turned black with ashes, rubble, and the remnants of the spells that tore the city apart.

I just loved the way she described a Paris that is at once reminiscent of its medieval heritage yet is set in an alternate 20th century with glimmers of history which seem familiar but isn’t.

As well as being a mystery, The House of Shattered Wings delves deep into the matter of faith. What happens when the thing you believe in the most rejects you. Bodard tackles this head on not only with Christian but also Vietnamese mythology. The character of Philippe, an Annamite exiled from his own land with its own religio-mythology in the Court of the Jade Emperor and its parallel history of colonialism, is fascinating in itself as we see him coming to terms with his loss and anger. I loved when his story of ancient Vietnam meets that of Selene’s Paris and Bodard does a wonderful job in tying the two parallel strands together in a credible way. You would think there might be a jarring of the two disparate worlds yet they complement and work together seamlessly. Philippe’s tenuous friendship with Isabelle, his sparring with Selene and his dealing with the Houseless, who initially took him in, and Asmodeus, the head of House Hawthorn, Silverspires’ nemesis, paints him as a complex figure, probably the most human with his mixture of compassion and street smartness. I found Madeleine, a human originally at Hawthorn saved by Morningstar when Asmodeus staged a coup to take over his House, fascinating in her despair and misguided memories, unable to get over her trauma and hiding her growing addiction, while trying to function in her job. But the two most intriguing characters are Asmodeus because he’s evil but with a secret agenda and there is always the spectre of Morningstar, more glorious, more powerful and more cruel than all the Fallen who haunt this book. In comparison, Selene is probably the weakest, always unsure and so hesitant for a leader of a House, but with the unwavering support of her lover, Emmanuelle.

Bodard’s plotting may have gotten the upper hand over her characterisation in this novel, it’s intricate and polished, her story substantial but wearing the research lightly, and I certainly wouldn’t have complained if it was longer, especially with her sublime prose. So I’m really looking forward to learning more about her varied characters in the sequel, many of whom seem to have incredibly intriguing back stories. And although the ending may have left me slightly wanting, I can’t deny that in The House of Shattered Wings, Bodard has created a richly textured world, intricate and beautifully written.

Do also check out Bodard’s In Morningstar’s Shadow, which includes 3 short stories that complement and is set before the events in The House of Shattered Wings, and Of Books, And Earth, and Courtship, about Selene and Emmanuelle. Lovely vignettes exposing more of Bodard’s talent. You can also read more of her stories on her website.

Maigret by Georges Simenon

12 August, 2015

I’m going to tell you everything, Uncle. I’m in big trouble. If you don’t help me, if you don’t come to Paris with me, I don’t know what will become of me. I’m going out of my mind.

Georges Simenon’s 19th novel featuring his eponymous detective Maigret which was first published in 1934 is my first foray into the famous detective’s world. In this episode of the detective’s long literary career, Maigret is enjoying his retirement in the countryside with his wife when his nephew, Philippe, comes knocking at the door late one night.

A rookie cop following in the footsteps of his uncle, Philippe is still young and naive and has found himself in trouble. On a stakeout for a drugs raid in Floria, a night club in rue Fontaine, Philipe takes the initiative to wait inside the club against orders and promptly finds himself with the corpse of the suspect on his hands. Rattled, he runs off leaving behind his fingerprints and is also seen by a witness. Having nowhere to hide, he begs his uncle for help.

And so begins a cat and mouse chase as Maigret returns to Paris to find the killer. Some of his colleagues, especially Detective Chief Inspector Amadieu who took over from Maigret, are none too pleased to find him back in his former workplace. However, when Philipe is arrested for murder, Maigret sets about catching the real culprit but this time without the authority of his badge. With the help of Fernande, a prostitute who frequents the Floria, Maigret must pit his wits against an intelligent and ruthless man who holds the strings to the case, and Philippe’s freedom.

Maigret was an interesting story because it showed the detective’s chase from the other side of the official fence. What struck me was the gritty, adult nature of the novel. There is sex, there is violence and real evil. Without being explicit, nevertheless the harsh reality of a criminal life and the psychology of the criminal mind is all there. This isn’t some cosy crime caper, it’s a gritty noir. It’s somehow difficult to believe that this was written in the mid-30s. There’s a lot of smoking, drinking and flirting going on. It’s a different world to what we know now, but it brings back a whiff of nostalgia mixed in with modern grittiness that I would like to revisit again.

At an event celebrating Simenon’s work, his son John said he wanted readers to become addicted to his father’s books. This short, sharp tale will do just that.